Smart Factory Case Study

Issues and solutions in the manufacturing industry from the Kanazawa Murata factory perspective (Part 2)

In the previous part of the online interview with Masashi Okamizu and Tsuyoshi Koyama of the Kanazawa Murata factory, who have been creating products using advanced technologies, we had spoken about how AI and IoT use was crucial in improving the efficiency of processes and back-office tasks as well as for the optimization of operational performances and equipment. IT tools that make use of these technologies have rapidly evolved, and industry 4.0, which was announced in Germany in 2011, has become more of a real possibility, making transitions of factories into smart factories a global standard.

This new wave of transitions has also started to emerge in Japan’s manufacturing industry, but how far has it penetrated, and is it actually in progress? We spoke about the current state and prospect, and not about its effect in the far future.

What are the obstacles that can be felt on-site concerning transitions into smart factories?

Smart factories are factories that aim to improve production output and production efficiency as well as improve the work process through utilization of digital data extracted from AI and IoT. Although the scale would be too massive if the transition were for the entire factory, “visualizing” various processing data and eliminating waste to achieve efficiency is the first step.

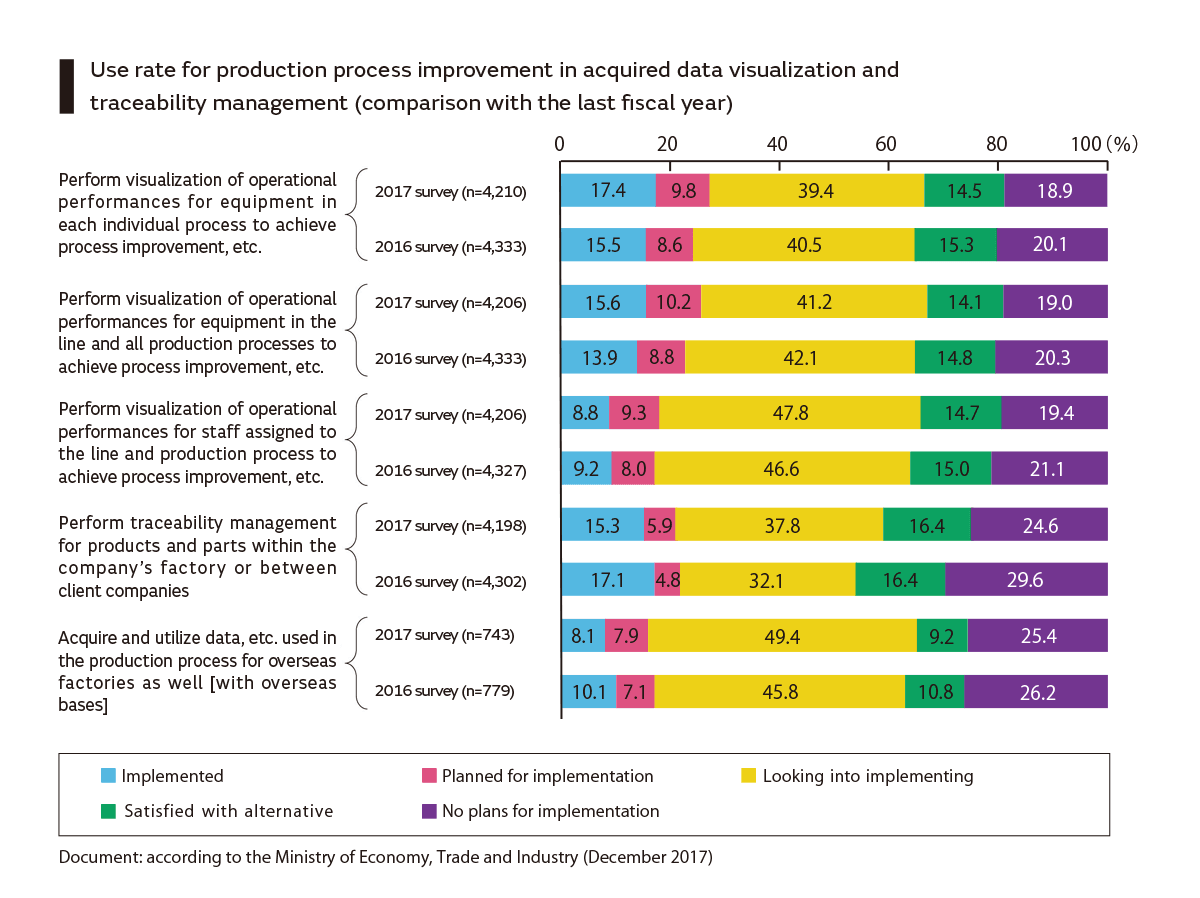

Internationally, the United States, Germany, and China are deemed developed countries in terms of smart factories, and the state of IoT introduction to products and processes in the United States is said to be about twice the amount of Japan (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications “Research Investigation Related to Verification of Multifaceted Contribution to Economic Growth Through Structural Analysis and ICT of ICT Industries in the IoT Age”). Japan’s introduction rate is relatively low, as can be seen in the following data.

The item “Perform visualization and process improvement, etc.” for equipment in each individual process and all production processes as well as operational performances of staff is included in the items on the left. Companies with “Implemented” are in blue while the rest with “Planned for implementation” and “Looking into implementing if possible” are companies that have not yet implemented the transition. This indicates that more than 80% of companies have not implemented the transition. It is quite obvious why transitions to smart factories are lagging in Japan’s manufacturing industry. “Looking into implementing if possible” which is in yellow, is an item that constitutes a majority of all items. However, Okamizu and Koyama, who are stationed at the factory, state that they feel they know why the transition has not been implemented.

Koyama: “Can the desired effects be achieved by introducing the latest expensive IT tools? I believe it is crucial to evaluate cost-effectiveness. Additionally, since the processes I supervise are mostly for prototypes and are basically steps where quality is prioritized, there are discussions on whether or not transitions are actually necessary.”

Okamizu: “Additionally, it is crucial to evaluate whether the IT tools really match or actually enhance the effects of our processes. Now, there is a large number of IT tools and we would like to select one that suits our processes.”

What are the elements that should be emphasized when transitioning factories to smart factories?

Currently, Murata has introduced a unique quality management database “PRASS.” However, Okamizu states, “We are capable of visualizing which lot went through which process, but it has not been introduced to all processes, and it is not complete.” Also, introduction of “PRASS” is difficult in terms of compatibility because processes that Koyama handles run on a different system.

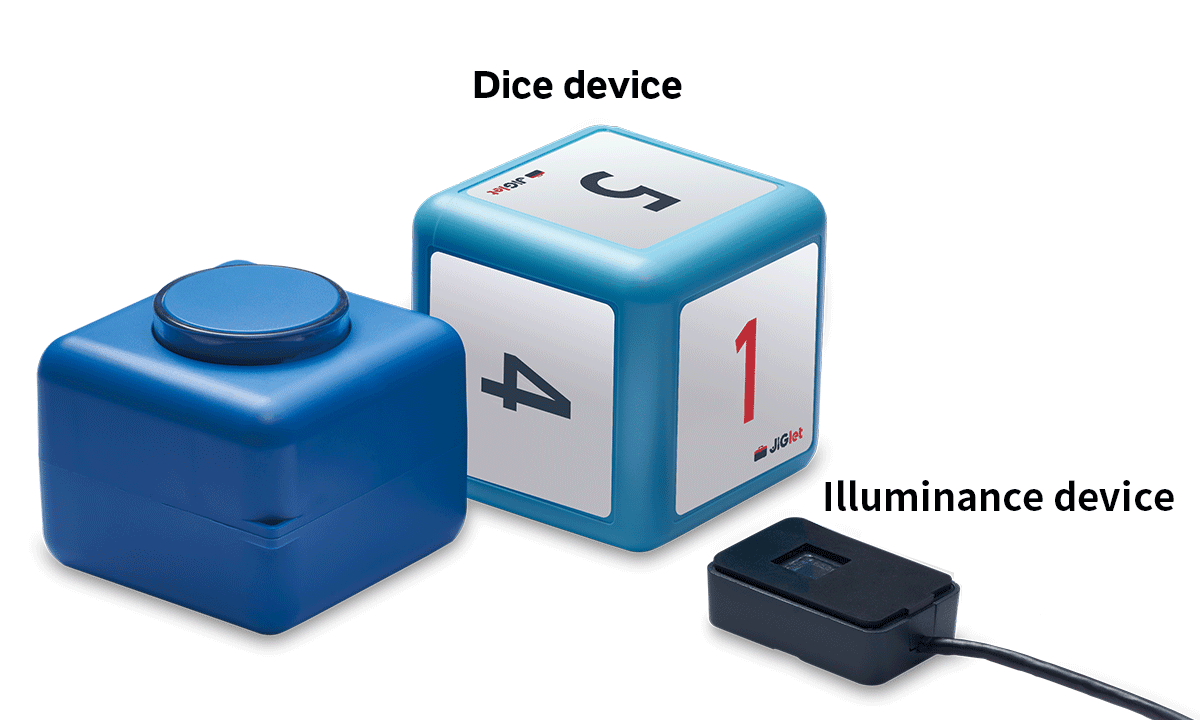

Optimization and standardization of work are issues that must be solved, but there are various obstacles for IT tool introduction. Under such circumstances, the Kanazawa Murata factory has evaluated whether to introduce the smart manufacturing support tool “JIGlet.*”

*The JIGlet discontinued its service as of the end of December 2024.

Okamizu: “In addition to its compatibility to our processes, is it easily comprehensible for our staff, and is the operation cost optimal? To identify these issues, we evaluated whether to introduce it.

We introduced illuminance devices in the process that lines up circuit boards, but we discovered that graphs could be created by automatically aggregating the operational performances by identifying the flickering of the rotary beacon light. This is the ‘variation in the operation rate.’ There are days when the operation rate is at 50%, while some days reach 80%. I was surprised at the difference. From now on, we plan to optimize equipment and staff by standardizing operation rates, analyzing the non-operation factor that leads to varying operation rates.”

In addition to illuminance devices, we also ran inspections of dice devices that aggregate and graph six events (example: non-operation factor). This system aggregates data by registering events such as “non-operation due to equipment trouble” and “non-operation due to human error” on the six faces of the dice device in advance, and when the staff changes the face of the dice during non-operation. We are then capable of easily visualizing which equipment stopped due to what factor as well as the time until resumption of operation.

Okamizu: “Installation of ”JIGlet” such as illuminance devices and dice devices is simple, and is optimal since anyone can operate it. We were able to see that intuitiveness is an important factor, even enabling staff with low IT literacy to operate it. On the other hand, the dice device is operated by the staff, and training on-site is also an important element.”

Discovery that visualization is a factor that increases motivation

On the other hand, Okamizu reflects that IT tool use brought about unexpected effects.

Okamizu: “Visualization of the operation rate was an element we gained from, but the effects it had on staff was a discovery. Staff that only performed processes they were assigned to now think for themselves since the operation rate had been visualized, and are now willing to discover solutions for improvement themselves. Of course, visualization of numbers may lead to severe evaluation, but I was surprised this led to an increase in motivation.”

The Kanazawa Murata factory is taking steps to transform its factories into smart factories by considering the introduction of AI, RPA (robotic process automation), and BI (business intelligence). Although we can expect production output improvement, process efficiency, and standardization of work, we seek to train our staff assigned for operation.

Okamizu: “Until now, our staff were assigned only to on-site work, but now, we have implemented debriefing meetings where they can share their efforts. By having our staff join these meetings, I believe they will be able to nurture their sense of participation, sense of responsibility, and motivation. I’ve been told they’ve become more confident in speaking in front of others.”

Koyama: “In addition to in-house training, we have created an environment where staff are capable of sharing their opinions using QC circle (improvement activity for small teams that allows voluntary management and improvement of the workplace). I would like our staff to acquire abilities to achieve solutions for improvement by analyzing issues at work by themselves.”

IT tools may provide solutions based on various data, but these decisions are made by people. To begin with, deciding which IT tool to introduce to which process to achieve efficiency is decided by people. This is why the Kanazawa Murata factory nurtures its staff. We may discover a solution for issues of the Kanazawa Murata factory as well as of the manufacturing industry when both transitions into smart factories and employee training interlock.

Related articles

- How to Fill the Gap in the Proficiency of Workers? Iwate Murata Manufacturing Edition (Part 2)

- How to Fill the Gap in the Proficiency of Workers? Iwate Murata Manufacturing Edition (Part 1)

- What Is the First Step to Converting a Regular Factory into a Smart Factory? Komoro Murata Manufacturing (Part 2)